[Note: Originally published on Substack with the subtitle, "The (very) rough first draft of Chapter 1, plus some back story."]

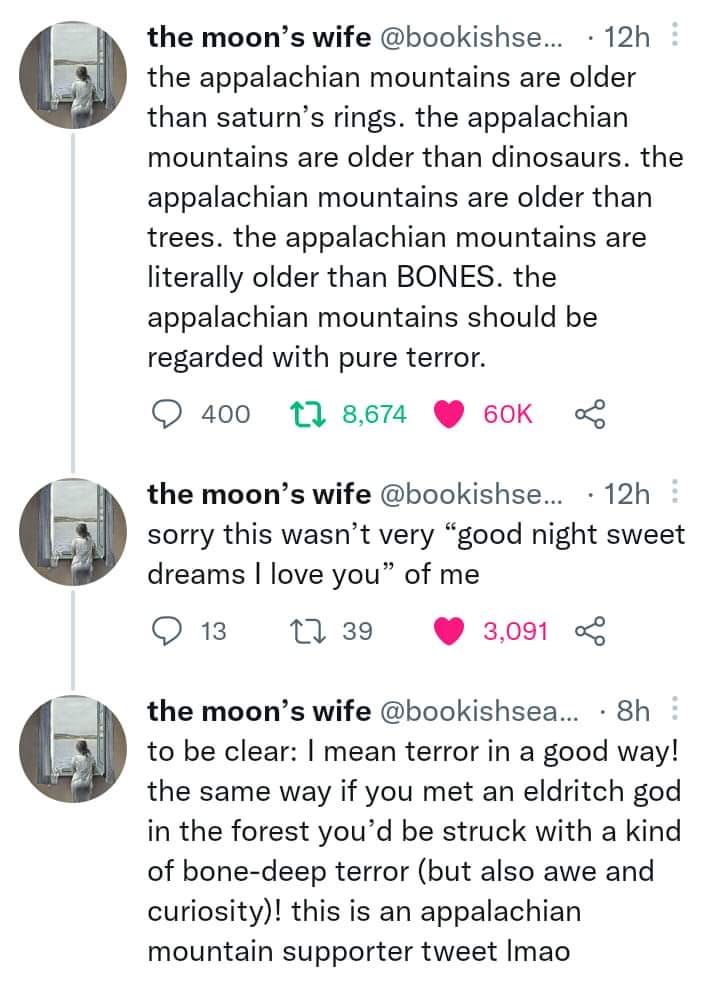

A couple of years ago, I stumbled across a meme asserting that the Appalachians are so old, we should be terrified of them.

The idea tickled my fancy enough that it lingered in my mind until a barebones idea popped into my head: In the long-ago day, the Bone Woman crawled out of the sun.

That was right around the time I attended one of Craig Martelle’s Indie Capstone retreats in Fairbanks. The very first night, I shared the line with Historical Romance author Melanie Rachel, and she loved it. Her kind words encouraged me to continue developing the idea.

My son and my bestie (who also occasionally serves as my editor) were kind enough to act as sounding boards, which was crucial in developing the underlying story world and some of the myths serving as the backdrop.

Eventually, that one line expanded into a background myth about a great battle between the gods, how the Appalachians were really formed, and what trouble those early battles created for the descendants of the gods.

I hope to one day turn all these wonderful ideas into a series called Gods & Monsters of Appalachia, set in modern-day western North Carolina.

So yes, this is Contemporary Fantasy, but on the dark side. It draws a little bit from a lot, including, among other things, Cherokee mythology, Appalachian folk healing, and the old mountain ways that are slowly disappearing.

What follows is the first inklings of a novel called Of Mountain and Bone. It’s a very rough draft of Chapter 1 (meaning, some of this is bound to change and/or be smoothed out as the rest of the story is written). Please let me know what you think in the comments.

For now, a warning: the Bone Woman has grown restless in her grave and her displeasure rumbles through the hills and hollers, stirring creatures to haunt the shadows of our dreams…

Of Mountain and Bone, Chapter 1 (rough draft)

The nightmare dogged Makenzie Walker for a solid week, beginning, as it always did, with unending rain and jagged lightning outlining the coal black night.

The rain coated her skin, sinking numbly into her pores. Harlan stood shivering in the garden, stripped to his skivvies, his string-bean thin body hunched against the cold. The mineral scent of rich, loamy soil mingled with the unfamiliar stench of rotting meat.

Something stood at the edge of the woods, in the nighttime shadows, whispering Harlan’s name.

Mack flopped over in her sleep, willing her brother to turn away before the unnamed unknowable stepped forward, before lightning flashed bright as a headlight and rendered it vividly, terrifyingly real.

Harlan merely stood there, his little boy body as still and bone white within the night as the thing at the edge of the woods. In the dream, Mack screamed soundlessly and extended her hand to him, her own fingers unnaturally pale.

Harlan, come back to me, please come back, sweetie, please be safe.

The thing stepped out of the woods, revealing itself, and Harlan crumpled into a twitching heap in the fresh-tilled mud, his mouth stretched wide in a soundless scream. Mack’s fingers scrabbled uselessly along her brother’s rain-slicked flesh as the thing loomed over them, its unholy visage leached of color in the eerie white-blue light streaking through the night. A hand with too many knuckles descended from the darkness…

A rasping squawk sounded in her ear, and Mack woke on a gasp, her heart a solid thump in her chest, beating time with the rain pounding against the tin roof. Her first thought was of Harlan, her baby brother, sweet Harlan who used to sleepwalk into the night.

Then something hit the window’s glass. She glanced over and spotted a huge raven perching on a tree limb outside her window, its feathers snowy white against the storm dark sky. It cocked its head at her, then spread its wings and launched into flight, disappearing quickly into the rain.

Mack flipped on the bedside lamp and wiped a shaky hand across her face. Her skin felt clammy and cold, as if she’d been in the rain again. As if she had, in her dreams, returned to the night when Harlan had transformed from a bright, active ten-year old boy into a zombie hiding in his own head.

The doctors had blamed the seizure, and over time, Mack had learned to hide the truth of that night even from herself. “There’s no such thing as monsters,” Dad used to say. In the light of day, Mack agreed with him. In the daylight, the only monsters she saw were human.

But at night, in the shadowed realm of her dreams…

A thin mewling drifted to her from Harlan’s room. Mack threw the covers off her legs, flipped on the lamp beside her bed. The digital clock read two thirty-three, and she realized what day it was.

Ten years since Harlan had folded into himself. Ten years since she’d stumbled after him in the rain and found him, shivering and alone, in the garden. Ten years since Dad found Mom collapsed on the bathroom floor, dead.

Mack shuddered. God. No wonder nightmares haunted her sleep. No wonder poor Harlan had been so restless lately. That night, she’d lost everything, their mother to an aneurism, their father to grief, and Harlan to whatever demons he’d seen in the woods.

Her brother had lost more, though. That night, he’d lost himself.

Quickly, Mack skirted the foot of her bed, trailing her fingers along the creatures carved into the wood, and hurried through the house, flipping on lights as she walked. She found Harlan in his room, curled into a ball under the quilt Mom made for him, a twin to the one covering her own bed. His fingers were knotted into fists against his chest and his eyes were squeezed tightly shut.

Mack perched beside him on the edge of the mattress and stroked a hand over his head, smoothing coal black hair away from his high forehead. “There now, sweet boy. Sissy’s here. Shush now.”

His terrified hum cut off abruptly and he turned his face into her hand. For a moment, she saw not the full-grown man he’d become, but an echo of the boy he’d been. Eyes bright with mischief, the daredevil smile he’d worn even in his sleep. Her heart ached, heavy with longing and sorrow. God, how she missed that little boy.

His hands loosened a fraction, and her soft, soothing words became an old, familiar song, one their mother sang to them long ago, before their family fell apart. A song of wilderness and home, of forgotten gods and a great evil, and of a mighty hero born of mountain and bone.

Harlan’s hand crept from beneath the covers and touched her knee, and his breaths evened into sleep.

Mack let the song drift away and, with a tired sigh, laid her head on his shoulder. His bones poked at her through skin drawn thinly around him, and she made a mental note to try to get him to eat more. The last of the tomatoes hung on the vine. She’d spotted two nearing ripeness in their garden out back, unfurling in soil fertilized with tears and madness and grief. Some late cucumbers, too, and a promising hint of orange tinting the sugar pumpkins’ rinds. Maybe she’d run into Sylva before work and check the meat specials at the Sav-Mor.

“Stewed ribs for supper?” she said, hoping for a response, hoping he’d open his eyes and grin his mischief at her, the way he used to in the before time, when they were young and innocent and had no idea the monsters were real.

Before Harlan wandered outside, before the unnatural thing appeared at the edge of the garden, before they’d lost half their family to death and drink.

Harlan’s shoulder trembled beneath her cheek, the only answer he could give.

She sniffed back a prickle of tears, refusing to submit to the old sorrow clogging her chest. Someone had to hold their tiny family together. Someone had to tether Harlan to the here and now, and care for him until he found his way home.

“Oh, Harlan,” she whispered. “Come back to me, please.”

She swallowed down the heartache and closed her eyes, allowing herself to drift into the images conjured by her mother’s song.

***

A few miles away, Talmadge Owle knelt beside the dead elk splayed along the road cutting through the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, just past the visitor center, examining the gouges torn into its flesh by the piercing blue light strobing from his patrol car’s light bar. Claw marks. Looked like a cat, but a big one. Mountain lion? Black bear?

He shook his head, hummed tunelessly under his breath. No, bigger than both, which ruled out pretty much every animal native to Qualla and the surrounding counties.

Tam held his hands above the marks, fingers spread wide, measured one against the other, and still couldn’t fit his fingers to the grooves. His mouth went dry, and he swallowed reflexively. Yeah. Whatever did this was a lot bigger than a black bear. And it was still out there, maybe watching from the forest, maybe waiting for him to leave so it could feast on the kill. Maybe looking at him, wondering if he’d taste as good as the elk.

What kind of animal left claw marks set that wide apart?

When you have eliminated all that is possible, he thought, and shook his head again. Helluva time to be quoting a fictional detective.

Footsteps rang against the asphalt, and something blocked the light, casting the elk’s corpse in shadow. Tam half turned toward the shadow’s source and saw the pudgy figure of Prescott ambling toward him out of the night. The Chief of Police had been in office less than a month, a big city outsider brought in from Houston to straighten out the mess left by the last chief. Not a bad man, just not somebody who understood tribal politics.

What Prescott lacked in political acumen, he more than compensated for in his understanding of the law.

When Prescott reached the corpse, he knelt beside Tam and jerked his chin at the claw marks sheering through the elk’s hide. “Any idea what did that?”

“Your guess is as good as mine.”

Prescott barked out a laugh. “Last time I was in the woods, I was a Cub Scout. Didn’t like it then, hate it now.”

Tam quashed the impulse to rag his boss about taking a job in the middle of what passed for wilderness in the Carolina mountains. “Humans didn’t do this.”

“Well, that eliminates a goodly portion of the people living around here, I guess.”

“Only most of them,” Tam agreed, one corner of his mouth curled into a reluctant smile. “I’d put it down to natural causes, a carnivore hunting prey.”

“But?”

“Never seen claw marks that wide.”

“Neither have I, but that ain’t saying nothing.”

“Another thing.” Tam pointed to the dark red marks marring the asphalt. “It was killed in the forest and dragged onto the road.”

“Thought you said a human didn’t do it.”

“Don’t mean one ain’t involved.”

“No law against dragging a dead elk outta the woods.” Prescott pushed himself into a stand with a gusty sigh. “Animal control’s on the way from Sylva in case whatever killed it’s rabid. Any particular way we should dispose of the body?”

“The usual. Bury it deep and hope whatever killed it can’t dig it up.”

Prescott ran a rough hand down his face, adjusted his hat. “Damn shame a young fellow like you ain’t out carousing with the women or whatever local folks do at the end of a workday.”

Tam’s mind drifted to a particular woman, one far beyond his reach, an old longing he’d long since resigned himself to bearing. He cut the thought off and stood. Before he could respond, a pair of reflective eyes appeared at the edge of the woods bordering the road. For a moment, the round, coal black face of a panther appeared in the deep shadows, then disappeared again.

A chill ran down Tam’s spine and his hand went automatically to the gun holstered at his hip. It was one thing to speculate about a predator watching you from the woods and another thing entirely to see one.

Prescott dropped his hand onto his own gun, his eyes narrowing on the shrouded forest. “What is it?”

Tam waited a minute, his gaze quartering the night, searching for the animal he’d seen. When it didn’t appear, he rolled his shoulders and turned away. “We go visit our family.”

“What?”

“After work.” Tam managed a grin as he forced himself to drop his grip on his service pistol. “The only place to carouse around here is the casino, and that’s mostly old white folk.”

Prescott’s mouth twisted into an answering smile, though his hand stayed where it was. “Now, that’s a lie. I saw a whole group of Koreans from Atlanta in there one day.”

“Old Korean folk,” Tam said. “Same thing.”

“Ain’t nothing wrong with old folks, son. I’m one myself.”

Tam snorted, then settled in for the wait. Headlights flared near the visitor center, though none came as far out as this. He kept his mind carefully blank and one eye firmly on the shadowed forest lining the road, made polite chitchat with the chief, and waited for another, more urgent call to draw him away.

Animal control arrived first. As soon as he recognized the vehicle, his shoulders relaxed under the starched fabric of his uniform.

When they were done, Tam walked back to his patrol car and closed himself inside. Only then did he let out a shaky breath. That panther, the claw marks. He’d heard a story once, years ago when he was just a kid, a story he’d overheard his parents discussing, back when his dad was a cop, before the drink overtook him as it did so many of the men Tam knew. He searched his memory trying to recall the specifics, and got the time fuzzed image of his parents talking quietly in the kitchen, the way his dad’s hand shook against the stained tablecloth, his mom’s quiet worry. Not much more than that.

Tam took his hat off, laid it out of the way, and raked stiff fingers through his hair. There was one other thing he remembered, a thing that had nagged at him for ten long years: the haunted look in Mack Walker’s big green eyes in the days after her mother’s death.

What did that panther and the dead elk have to do with the Walkers?

Try as he might, Tam couldn’t quite make the connection, which left him only one choice. He’d have to visit the old man, whether he wanted to or not.

***

In a hotel room across town, Candi Magill leaned against a window overlooking the parking lot below. The glass reflected her image back to her. White-blonde hair cut short and finger-combed, the thick makeup outlining her pale blue eyes, hollow cheeks, and a slender build under a cropped t-shirt and low-slung jeans. Her bones poked through the fabric and her belly whined. She shushed it with a reminder that she’d feed it later, after she took care of business. Maybe she’d even have enough to splurge on the casino’s buffet, if it was still open when Darryl got through with her.

Her reflection smiled at her, and she smiled back.

The window gave her a good view of a fancy man standing in the middle of the parking lot. She lifted the joint she was holding, watched the tip smolder in the reflection as she sucked on it. He was wearing a three-piece suit and one of them old-fashioned hats. Whatsit? She snapped boney fingers against her thigh until the answer popped into her head. A bowler hat, black like the suit. Black like his shoes. Like his soul, if something like him could have a soul.

She smiled at her joke. An inside joke. Nobody else’d get it. She’d given up on that years ago, getting folks to understand. Only one that ever had was Granny Magill, and that because they were of a kind.

The man’s head tilted, revealing his pale, every-man face, and their eyes met, his as black as the night in the face he showed to the rest of the world. She could see through that face right to his heart. No, right to his true face, the thing she’d seen just once before in the real world, and more than she cared to admit in the visions that whipped through her when she least expected.

The last time she’d seen it in the here-and-now, she’d lost the only friend she’d ever had. The only body outside of her granny that didn’t care a whit about Candi’s odd little quirks.

“I know what you are,” she whispered. “I know what you’re trying to do, and it ain’t gonna work.”

The man’s mouth worked for a second, like he wanted to say something back, then he went back to standing there, looking up at her while cars zipped past him on their way in and out of the hotel’s parking lot.

She took another drag of the roll, held it longer than she should’ve. Some of the pain eased away and a pleasant fog drifted around her mind, cushioning it. She dug a small stone out of her pocket, a special stone with a hole drilled through it by water and time, and held it up to her left eye. The man’s mask fell away, and she saw him clearly despite the mist clouding her head.

“I see you,” she said. “You can’t fool me.”

The door opened behind her, and Darryl walked in still wearing his uniform. He was a tall man and handsome enough, in his own way. Best of all, his hair was nearly as blond as hers, his eyes a murky green.

That was important, she reminded herself. Important not to look too much like the only man who’d ever been kind to her.

“Who’re you talking to?” he said, his round face crinkled into an odd little smile.

Not odd like her quirks. Just Darryl odd.

She turned and held out the joint, wearing her reflection’s smile. “Nobody but you, handsome.”

He took the joint and lifted it to his lips, and Candi pulled the curtains over the window, careful to cover every last inch of glass.

***

A soft rain began to fall around the Walker house, bringing with it a damp chill. Mack shivered in her sleep, her dreams caught now not by nightmares but a jumble of random memories pulled from the deepest recesses of her subconscious.

Wind whispered through the forest beyond the garden, and a green-black shoot sprang from the soil between two rose bushes outside Harlan’s window. A pair of leaves unfurled from the shoot, each narrow and jagged, and a delicate tendril emerged between them, its end probing the moist air.

The plant shot up another inch and emitted a second set of leaves, giving the tendril enough height for it to curl around the nearest rose branch. Minute suckers developed on the underside, leaching nourishment from the rose’s sap. The branch shriveled and blackened as the tendril flourished around it, sapping life from the rose to fuel its own growth.

One limb was not enough. Two other tendrils shot from the hairy central stalk, each choosing a fresh rose branch as its host, and soon, the plant had wound around both roses, its own unnaturally dark flesh well-hidden by the more robust growth of the roses. A bud appeared at the terminus, snuggled between the late summer, blood-red blooms of the Mister Lincoln tea rose sheltering it. The bud cracked open, and from its withered, rust-colored petals emerged dozens of tiny insects, each monstrously different from the next.

The insects spilled over the roses, onto the house’s siding, into the soil, seeking cracks in the walls and foundation, the windows, the doors. Some died when the rain blew into them, others when more benevolent night creatures preyed upon them.

The thing the shoot had become did not care how many were sacrificed, only that one succeeded where the others failed. It only takes one. Content that it had done its duty, it surrendered to the rain and died.